This is an essay I found on my computer that I wrote in 2014 for Bergdorf Goodman magazine, that’s impossible to find on the internet. It’s striking to me in a number of ways—the consistency of my thinking (yes, I’m set in my ways!). But, sadly, many of the bars mentioned are no longer: The Orchid Bar (in the old Hotel Okura), the Rusty Knot, Harry’s in Florence, the Tyroler Hut in London. Glenn O’Brien, who edited the piece, and is still missed, is now raising a glass at the cocktail party in the sky.

Increasingly, it’s harder to find a straightforward bar: they’re too fancy, too loud, people are too distracted with phones, all the usual complaints about modern life. And also people just drink in dark rooms the way they did in the old days, which is probably a good thing. I don’t normally run old stories, but you already got a newsletter this week so think of this as a drink on the house.

Hope you like it,

D

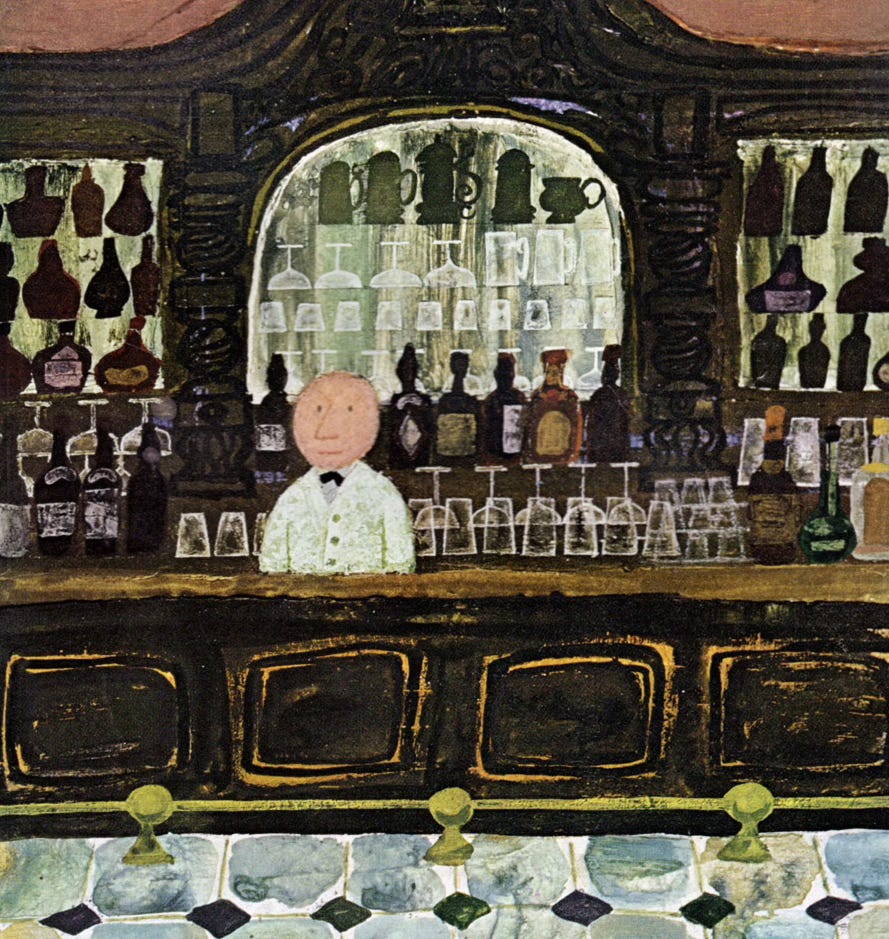

Bars have endured because people want to drink. They can do this at home, of course, but most prefer to drink in the company of others, some of whom, ideally, are good looking. Now that we’ve got that prevailing truth out of the way let’s consider what distinguishes the good boite from the bad. The most important thing about a bar is that it suggest the better nature of drinking: conviviality, lack of inhibition and a basic surge of optimism. It should not remind you of the imbibing’s downside: cloudiness, regret and morose Willie Nelson songs. A good bar feels like the first sip of champagne; a bad bar feels like the last slug of tepid beer. You want to be in a bar where somebody goes to celebrate a new job, not to forget they got fired.

This equation proves hard to master, so when you find the right one stick to it. It’s worth cultivating the status of a regular, though it’s a curious sensation when you’re first recognized by the bar’s staff. You have to confront just how much time you’ve spent on the rail devoted to the drinking endeavor. In that time you could have watched every episode of a critically-praised cable drama—twice. Or have read that long French book about economics everybody’s talking about.

It came as a surprise to me when the owner of a bar I frequented in my heavier drinking days told me about his initial speculation about my presence there. “We would be having our weekly meeting,” he confessed, “and you’d be sitting in the booth by the door. This was before I knew you, and I asked them Who is that guy? Are we even open?” All of which is to say, it’s probably better to be at a bar when it opens than when it closes.

This is why a relationship between bar and guest is an intimate one. Bartenders know as much about you as your analyst, your accountant or your ex-girlfriend. Good bartenders understand human frailty, that is, after all, what propels their trade. Use that bracing familiarity to found a professional relationship. Tip generously, in cash, and don’t insult their craft by ordering a pink drink. He’ll also understand when you’re taking a well-earned break from the hard stuff and opt for a club soda.

Other rules that will serve you sell as you seek a good bar: Themes are generally not good. They’re facile and distracting. Though there is a bar in London with an Austrian alpine ethic that is one of the more compelling places. If you’re in the very specific mood to hear “Edelweiss” sung by the elderly owner in his Lederhosen, accompanied by synthesizer and an array of cowbells, then you’ve found your spot.

Also: televisions are not good. They might attract grown men wearing the jersey of a sports team in public, which is not a good direction for civilization. Of course, there are times when you must watch a game. That’s fine, but order modestly, especially if they serve food. A good rule of thumb is that if there’s a TV in any establishment then don’t order fish.

What else is important to a good bar? Women, of course. A bar without them feels dangerously like a locker room. Better to head somewhere the fair sex feels more at home. Conviviality is good, but no bar should be so loud that you have to shout. In general, you should not be afraid to order a glass of wine in a bar. If you fear that the bartender is going to be pouring from a huge bottle of plonk then that’s not a promising sign. And whatever snacks they serve should not turn your fingers orange.

I’ve always preferred small bars, like those you find in old European hotels. Eight seats is good, five seats even better. At a smart bar in Florence not only do they serve the rarely seen classic Bull Shot, they bring the beef broth (don’t be frightened!) straight from the kitchen to mix the drink—now that’s how to do it. At Harry’s in Venice they might bring you a little grilled cheese from the kitchen between drinks. At the Orchid Bar, an incredibly little bar in Tokyo, they know that a martini should be gin and stirred until it’s fiercely cold, the way God intended. With a twist of lemon, of course. But you already knew that.

A good bar is usually dim—but doesn’t suggest that the darkness is obscuring something. In the end, a good bar is a refuge, a respite from a world moving too fast. Humphrey Bogart famously said the world is three drinks behind. A good bar gives you a chance to catch up, and the strength to venture forth.

In my 20s it was college/dive bars for cheap drinks. In my 30s it was restaurant bars for food and drinks. In my 40s it was brew pubs for local IPAs. Now in my 50s I'm back to dive bars.

“A good rule of thumb is that if there’s a TV in any establishment then don’t order fish.” is the kind of inside baseball I’m here for.